No Scientific Cliff Edge Of 12 Years To Save Planet (or 18 Months) - Can IPCC Challenge 'Deadlines Make Headlines' Misreporting?

Robert Walker

Yes there is much we need to do and can do. As we ramp up on pledges quickly we reduce future impacts of droughts, wild fires, hurricanes and other climate related local disasters. We will reduce the effects of sea level rise, and avert warming levels likely to lead to millions of climate migrants (chapter 3, section 3.4. 12 and Figure 3.4 page 246). These actions are also good for our economy and better for biodiversity. By staying within 1.5°C, we can save coral reefs from near extinction, and reduce the amount of adaptation needed for many ecosystems.

But the IPCC never said we risk human extinction or collapse of civilization. Their example of a worst case path (Box 8 of chapter 3), which we are not on, is one in which the world still produces enough food for everyone through to 21 00 though with reduced food security. It would be pretty much as it is now, normal governments, widespread literacy. Yes, that worst case future has a major reversal of the global sustainable development goals, poverty reaching new highs, reduced quality of life. But not a desert planet without kangaroos or humpback whales, agricultural crops or garden flowers. Nor one that has lost technology, and we'd still have the internet for sure (it's very robust because of its distributed design), space rockets, airplanes, skyscrapers, submarines etc.

If you are skeptical of this - and I am not surprised if you are after all the journalistic hyperbole - have a read of their Box 8 of chapter 3., which I'll also discuss more later on.

Nor do they give any fixed deadline. They can't, the science doesn't support any idea of a fixed "cliff edge" that we will fall over at some future date. Have a listen for yourself to the press conference and what the co-chairs said as their summaries in 2018:

If you want to go into it in more depth, I recommend you check out the Technical Summary. That is written by the IPCC scientists themselves. Or, if you don't have a strong scientific background, try a careful read of the Summary for Policymakers, The final draft is written by politicians, but with the aim to present the content clearly for non scientists. It gives a fair summary and is co-written with scientists until just before the final draft.

The journalists who repeat "12 years to save the planet" in their news stories never cite this to the IPCC report by page, section number or quote. Nobody could because this climate slogan is not there.

This has become so serious that five sociologists with expertise on human geography, climate change and public policy wrote a strongly worded article about it as Nature comment:

The authors say the IPCC should break from their traditional strictly non partisan, non political stance to speak out about this misrepresentation of the report. What happens if we go slightly over 1.5°C, when it will be clear to everyone that society didn't collapse and humans didn't go extinct? For most of us, the world would continue to feel much the same as it is today. Will the public continue to trust the IPCC reports after that? Of course the IPCC never said those things, but how can the general public be expected to know this when they are so widely misreported?

There are plenty of reasons for urgent climate action. In only three years of new policies under the Paris agreement, we have already knocked more than a degree off the projection for 2100 (down to 3°C). We are already ramping up on those commitments too. We can do this!

This has already greatly improved our prospects for the rest of this century. We need to keep this up, but let's recognize what we have already achieved with the pledges so far.

To take one example of many, at 4.9°C we risked a world so hot that by 2100, there would be times when the heat combined with the moisture from paddy fields would make it impossible for Chinese farmers to work out of doors for more than a few hours before dying of heat exhaustion (see North China Plain threatened by deadly heatwaves due to climate change and irrigation). There would be similar issues in parts of India, the middle East, Southern US, the Persian gulf, and other places around the world. At 3 °C this risk is greatly reduced, and we have achieved this in a way that leaves plenty of margin to ramp up to more ambitious pledges in the near future.

The authors of the paper argue that we do not need this deadline-ism for action and that it can actually be harmful to our prospects for mitigating climate change. They are speaking up against misrepresentation of the science. Of course we need decision deadlines, and target dates for actions, but with a scientifically accurate framing of the debates that lead to them.

They go into details in the paper itself. They agree that these supposed scientific deadlines do energize some people, but they cause others to give up and despair with the belief that the situation is hopeless.

Myles Allen, who was the coordinating lead writer for chapter 1 of IPCC report in 2018 (framing and context), not one of the authors of the new paper, made a similar remark on April 18 2019. He spoke up about this in his op. ed. in The Conversation:

Today’s teenagers are absolutely right to be up in arms about climate change, and right that they need powerful images to grab people’s attention. Yet some of the slogans being bandied around are genuinely frightening: a colleague recently told me of her 11-year-old coming home in tears after being told that, because of climate change, human civilisation might not survive for her to have children.

Why protesters should be wary of ‘12 years to climate breakdown’ rhetoric in The Conversation:

I have come across what he talks about here so often in my voluntary work helping people over the internet who are scared of false and exaggerated doomsdays. As Myles Allen says, many young teenagers believe these deadlines.

To add to what he says there, in my experience highly educated adults do too. There are many younger kids who take all this so literally, they are convinced that they will not live to adulthood. Adults wonder about what kind of a world their children will grow up into. Some are stimulated to action but some panic, get scared, need therapy for climate anxiety with diagnoses of General Anxiety Disorder, and have difficulty continuing to function, crying, panicking, or they may wonder where to migrate to, to find a safer spot in the future world.

As a science blogger I have written many blog posts to help these people, doing my best to counteract the misleading climate change news in the press. This is one that I did about how ours is a world full of nature on all the scenarios. We do not face a future without giant pandas or humpback whales, or without insects, ladybirds, wild flowers.

As a science blogger I have written many blog posts to help these people, doing my best to counteract the misleading climate change news in the press. This is one that I did about how ours is a world full of nature on all the scenarios. We do not face a future without giant pandas or humpback whales, or without insects, ladybirds, wild flowers.

Many of those I help do not realize that the world has a huge food surplus at present (e.g. food stockpiles, stock to use ratio, of over 30% of yearly production for grains, 50% for sugar, see FAO Cereal Supply and Demand Brief and more extensive summary for two year period ending 2018).

All world hunger is due to politics, and economics. The food is there but the hungry people can't afford to buy it.

We can still feed everyone, through to 2100 on all the scenarios, though with reduced food security and damaged nature services in the least sustainable scenarios. I wrote this, expanding on a comment by one of the speakers to the IPBES report earlier this year:

One of the places where we can make the biggest difference in food supply is in Africa because of its inefficient agiriculture. The "Green revolution" that has revolutionized agriculture on all the other continents, for the most part has passed Africa by. It could produce ten times as much food if it was optimized like the best agriculture in the US and China. Most of the predicted population increase is in Africa.

Worldwide our population is leveling off, no longer exponential. Not leveling off due to scarcity as used to be predicted but due to prosperity. Reduced child mortality, better education, and greater equality of women in decision making all play a role here. Wth fewer children dying, parents have smaller families because they know that they have a good chance of surviving to adulthood.

Japan is one of the nations with the most rapidly declining populations. We are already at peak child, or close to, we jave roughly the same number of children as a decade ago and the world population continues to grow rapidly mainly beause of the extraordinary advances in health care. Worldwide we live ten years longer than 50 years ago. For some countries it is 20 years longer, for China it is a truly remarkable 30 years increase in life expectancy from 1960 to 2010.

This expands on some of that, and goes into other things such as resources and energy return on energy invested for fossil fuels compared to renewables

See also

One of the main messages of the IPCC report was that it is not just up to the governments of the world. We are all in it together. Our individual choices, how we go to work, the energy use, even down to the food we eat. Here is Debra Roberts talking about our power as consumers and our life choices:

(click to watch on Youtube)

Either way, whether energized to action by these "cliff edge" false deadlines, or numbed into hopelessness, the public's actions are based on misleading ideas which can lead to them making bad policy decisions (the authors of this paper list various examples of how policy decision making could go wrong as a result of this misunderstanding). Neither is needed. What we need is to build consensus and enduring bipartisan solutions. They say that this is a misuse of the report and that the IPCC should challenge this.

But who is reporting this Nature paper? As far as I can see, none of the big mainstream news sources have so much as mentioned it in passing.

Instead the journalists are "upping the ante" to 18 months, quoting Prince Charles - who is not a climate scientist, but what's more, he was using hyperbole, like "I could eat a horse". See my

He was actually giving an optimistic up beat speech about how there are various things going on that mean we are likely to have major changes in place already by the time of the 2020 major climate conference.

The 18 months there is just the time until 2020 when the nations who signed the Paris agreement in 2015 meet to increase their pledges for the first time, and share experiences with each other and the public. They will do this again in 2025, 2030 and so on. And there is nothing in the report about “Saving the planet” as we’ll see.

Things are looking good for that, many countries expected to increase their pledges, including China which recently affirmed its commitment to increase its pledge as well as supporting the Green Climate Fund to help with adaptation of the developing countries (a few years back China transited from a developing country to a developed country and now is in a position to be one of the donors to the fund).

We probably won't get down to 1.5°C right away with that, but for sure will get below our current 3°C target for 2100. Then we have future pledges in 2025 and 2030, each time building on the experience from the previous 5 years as well as technology advances since then that are likely to continue to hugely reduce the costs of renewable power stations and introduce new technology (for instance carbon capture and utilization).

Nor are there any emission targets for 2020 itself. The models studied by the IPCC all have the yearly emissions steady, or slightly increasing through to the early 2020s when they start to fall.

Of course politicians can and should set deadlines. The 2020 and 2025 dates are deadlines. The UK target of zero emissions by 2050 is a deadline. But it's we, the public, and the politicians set these deadlines.

What the authors think the IPCC need to speak up against is the idea that there is a date that is hard coded in science. An immovable date that cannot be discussed by politicians. Like the "Dangerous Cliff Edge" sign that you put on a road before a cliff edge.

Dangerous Cliff Edge, County Clare, Ireland by Anna & Michal

There is no date of that sort in the report. They found no tipping points of that sort at all. There are tipping points for the Greenland and West Antarctic ice, but these unfold over thousands of years, plenty of time to step back from that particular cliff using carbon capture and storage over many centuries.

Techy detail: Greenland ice has a tipping point between 0.8°C and 3.2°C, median 1.6°C. If we cross that tipping point (it is possible we already have) the result is very dependent on future climate, between 80% loss after 10,000 years and complete loss after 2,000 years. The threshold for Western Antarctica (and sectors of Eastern Antarctica) is hard to estimate but probably between 1.5 to 2°C. Most of Eastern Antarctica continues to accumulate ice, as it did through the previous interglacials. See 3.6.3.2 Sea level

The melting of the Arctic sea ice is not a tipping point either, according to the report (see 3.6.3.1 Sea Ice). As soon as we reach zero emissions the Arctic ice then is in steady state and will slowly being to heal as some of the excess CO₂ leaves the atmosphere. The idea that the climate will suddenly go haywire once all the Arctic ice melts is junk science. The ice only melts in summer and if the entire Arctic melts one year, then that means it freezes much faster the following winter (the ice forms an insulating layer which stops the oceans from freezing so quickly in winter).

If you have read a recently published paper suggesting a major impact from the Arctic ice albedo effect - this is leading edge work, which in science is like a conversation and this particular paper is an outlier in the debate with significant issues. The Arctic is getting more absorbing of heat but not as much as you'd expect because of increasing cloud cover. Meanwhile other areas such as the southern Pacific around Australia and Malaysia are getting significantly brighter as a result of global warming and you have to look at the whole picture, which actually is of a planet that is getting slightly brighter, less absorbing of heat as it warms up. See my:

They found no other climate tipping points.

As for ecosystems, the corals go nearly extinct at 2°C but no other major ecosystem is affected. They do not turn to deserts either, sponges may take over for instance.

(click to watch on Youtube)

Some corals such as the ones in the Red sea will survive, because due to a historical accident they are pre-adapted to higher temperatures. Some individual species of coral in the barrier reef are more resistant than others, and corals can certainly adapt given time, since there is a range of several degrees in the temperature conditions that corals do survive in. The issue is that local corals are so finely tuned to local conditions they die after just the minutest of increases. So the problem here isn't really a coral species hard edge for temperatures either, it is more a question of whether they can adapt or move in time. It might be that humans can help to some extent by translocating them artificially, but this is not easy if you have an entire coral reef to maintain. For more about the corals, with a focus on the Australian great barrier reef, see the second half of my

Other coastal ecosystems such as sea grasses, kelp forests, and salt marches span wide ranges of conditions. However, like many of the terrestrial ecosystems, they would be largely unaffected, with many of the species surviving over a wide range of conditions. There are vulnerable spots near the warm edges, however again other species will take over in time, and fish especially can move easily in response to climate change.

Even the mangroves, sensitive as they are, survive a 2°C rise fine. This is a major thing to happen to our world, to lose most of the corals, but it does not endanger the planet as a whole or human survivability.

This is another article I'm writing to support people we help in the Facebook Doomsday Debunked group, that find us because they get scared, sometimes to the point of feeling suicidal about it, by such stories.

Do share this with your friends if you find it useful, as they may be panicking too.

If you read the report itself , they do give an example worst case (Box 8 of chapter 3) and it is one with increasing poverty by 2100, reduced food security, but we still can feed everyone on every scenario and it is still a civilization. I will discuss it later in this article

You can read the report for the details, either the Technical Summary (for those with a decent scientific background), or the Summary for Policymakers,s (for non scientists). See also my

For an overview they have a five-fold classification:

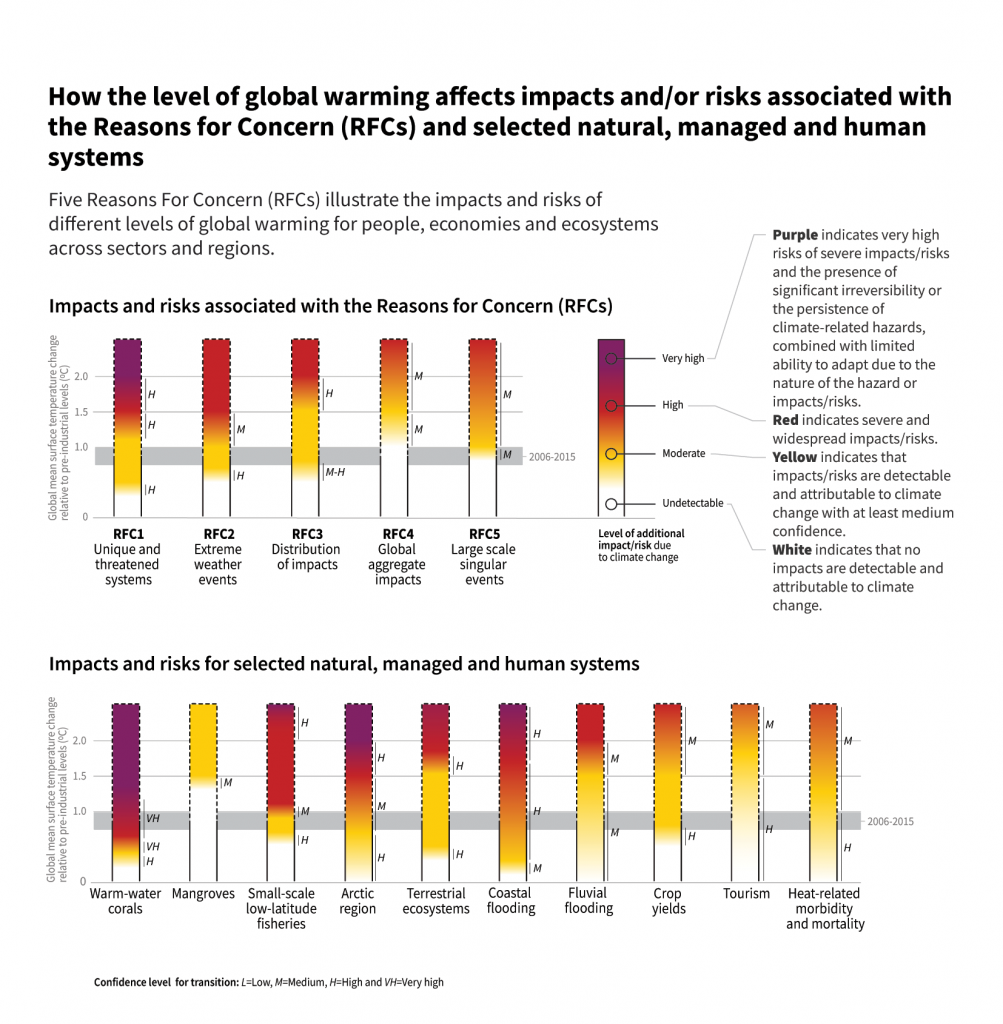

Then they have a similar graph for selected ecosystems and other related risks, at the red level there is a high risk of impacts. Here, the temperatures are shown as horizontal grey lines for the present day (gray bar) 1.5°C and 2°C. The yellow area means that we start to notice the effects, at red they are severe risks with widespread impacts, and as it shades to purple, there is significant risk of irreversible changes and there is limited capability to adapt, for instance many of the coral reefs are already lost at 1.5°C, and it's hard to prevent this, while at 2°C then nearly all are lost.

Their main focus is on the difference between 1.5°C and 2°C, because that was their remit, what they were tasked to do. They only briefly mention the effects at 3°C. For that we need to wait for the next report in 2021. The previous IPCC report did cover 3°C, but it's clear from the 2018 report that science has advanced too much since then for it to be a fair comparision to directly compare what it said about 3°C with the results of the 2018 report for 1.5°C and 2°C.

At 1.5°C it will feel very similar to what it is now to most people unless you live in one of the most affected regions - for most of those sectors it is in the yellow region where you start to notice differences (like the changing climates many of us are already noticing but more so). At 2°C many will start to notice significant differences and at 3°C the world will feel very significantly different. But none of them are desert worlds or uninhabitable worlds. Ecosystems change to other ones, e.g. tropical forest to savannah, or in northern Europe the species distributions of forests change with more deciduous trees and fewer conifers. The higher northern latitudes actually have improvements in agriculture.

One of the biggest impacts on terrestrial systems between 1.5°C and 2°C is in the Mediterranean and the regions around it (including southern Europe, northern Africa and the Near East). It is possible (though not certain) that above 1.5°C, large parts of the Mediterranean biome transform to desert, a change unparalleled in the last 10,000 years - that's in the executive summary of Chapter 3. If this does happen, of course people can live in deserts and there are ways of doing agriculture too, with remarkable work in greening deserts and you can mitigate such effects with improvements in water management and so on, or people can move to parts of the world that have become more habitable. This is still a matter of policy decisions and beyond the remit of science, whether we need to stop the Mediterranean region transforming to a desert biome.

We already have climate migrants, for instance in Bangladesh, due to sea level rise. It's mostly internal. How much of this happens is hard to assess as it depends on how much they can mitigate it. They may be able to stay where they are especially if the Green Climate Fund helps them to mitigate the effects more with funding and technology transfer. The more developed countries can help prevent a climate refugee crisis. By way of example, Netherlands engineers are already helping Bangladesh to adapt to rising sea levels.

They cover this and the differences between 1.5°C and 2°C in the chapter 3, Impacts of 1.5°C on Natural and Human systems. For those with a less scientific background see the section Projected Climate Change, Potential Impacts and Associated Risks in the summary for policy makers.

For the 3°C impacts, we will need to wait for the next report in 2021, because science has advanced beyond the last one to the point that we can't directly compare what they say about 3°C with what the 2018 report says about 1.5°C and 2°C.

However we also have the full IPBES report. The draft chapters are now available online. Also see this which I wrote based on the summary for policy makers and the press conference:

With that background you can understand why their report has no hard deadline. The IPCC is resolutely non political. They act similarly to scientific expert witnesses called to testify to a government select committee. They fulfill their remit, to present the scientific evidence. They leave all matters of policy decisions to the politicians.

In the report, they presented four different ways to get to 1.5°C. They made it clear that these are just some examples from an almost infinite variety in possible future policies:

All of them have increasing emissions year on year for the first few years through to 2021 because it takes time to turn things around. All climate scenarios are almost indistinguishable for the first few years. But they differ in what we do after that.

The first of these, P1 required 45% reductions by 2030 (40–60% interquartile range) ramping down to close to zero emissions by 2050. (Technical summary page 33, chapter 2 section 2.2.1 - it is called LED or Low Energy Demand in chapter 2).

This mainly relies on CO₂ reductions but also uses a measure of reafforestation, land conservation, restoration and management, and sequestration in sea margin habitats (such as sea grasses, mangroves, and salt marshes), This is the path that politicians have favoured.

The second one, P2, (S1 in chapter 2) delays the reductions a little, but still uses mainly reafforestation, conservation and other land used based negative emissions

These paths depend mainly on reducing CO₂ emissions. If we continue with just the 2015 pledges and with no carbon dioxide removal (CDR in the report) then we reach the limit for 1.5°C (with a margin of 0 to 9 years) by 2030. That's why they say we have to increase pledges significantly by 2030, either that, or do significant carbon dioxide removal through land use change, or do both, to achieve the 1.5°C targets.

Now we can do very significant CO₂ removal through land use change. In case this seems impossible to you I'd just to briefly mention the Chinese Loess Plateau project. They restored an area the size of Belgium - you might think this is image manipulation, but no, this is a real project:

Loss Plateau in September 1995

Loess Plateau (Loess Plateau - Wikipedia) in September 2009. See Greening the desert (Greening the desert)

This documentary, “Hope in a Changing Climate” - by the soil scientist John D. Liu (2009) covers the project right from the start when it was almost a desert landscape. The second half of the video covers how similar projects have transformed regions in Ethiopia and Rwanda.

Video here:

(click to watch on Youtube)

The FAO has a special focus / section on soil health called the "Global Soil Partnership" which is very active worldwide helping to preserve and restore soils. It was a major issue a few years back and there has been a lot of progress in tackling this both in actually doing something, programs to help farmers improve their soils, and research to know how to do it, and in getting data including the first map of global soil carbon content, so that they can assess progress. This is connected with the urban myth you often hear that we are going to run out of top soil in 40 years. Actually, no, that never was possible. There are areas of soil degradation and areas where it is acumulating. But there are serious issues of soil health worldwide, and the Global Soil Partnership was formed to deal with these. For details and for many inspring examples of other projects like the Loess Plateau one, see my

The other two pathways there are ones where we do not do much until we exceed 1.5°, but then ramp rapidly down to zero and then do negative emissions with carbon capture and storage. We've got power plants that burn biochips, and commercial scale industries that capture CO₂, and the Drax biofuel power plant in the UK has just become the world's first to do both. Britain's Drax becomes world's first biomass plant to capture carbon . It is just a pilot so far capturing a ton a day.

This video about the Adu Dhabi power plant shows that we already have carbon capture and storage going on at an industrial scale:

This steel plant captures 800,000 tons a year and plans to expand it to 2.3 million by 2025 and 5 million before 2030. The Sleipner gas fields CO₂ injection in Norway can store 600 billion tons. That alone is enough to store all the CO₂ for the 2018 IPCC report, even the fourth of their paths with extensive carbon capture and storage, so there is no problem storing it if we can pipe it to suitable reserves.

Biofuel burning has often been criticized on the basis that it involves using agricultural land for biofuels, or that if it burns trees, they are replaced on too long a timescale even if taken from sustainably managed commercial forests. There are no such problems with crop residues or sawdust, or wood that is in the form of offcuts or sections of trees that can't be used in other ways, which likely decompose and produce a fair bit of methane or carbon dioxide anyway if not burnt. But is there enough of this to justify large scale power plants? The Drax power plant in the UK imports wood offcuts and residues from the United States to keep it going.

One interesting development recently is CBECCS - a mixed coal bioenergy gasification with carbon capture and storage. The idea is to convert coal power stations to use crop residues (so avoiding the issue of crops that are grown just for bioenergy, or felling forests for bioenergy). With a mix of 35% crop residues then the power plant produces electricity with net zero emissions. The biomass fraction can ramp up when more biomass is available. This could be deployed in China, Brazil, India and other places with abundant crop residue biomass. The farmers could sell the crop residues to the power stations. The CO2°Capture has the benefits of also reducing the air pollution which is such a major issue in India and China, while at the same time providing net zero emissions energy.

It could be used in regions that produce large amounts of crop residues and also have large local energy demand and serious local air pollution. In China the Huabei and Yuwan basins are especially promising and also have abundant sequestration capacities for CO2 (estimated at 264 gigatons and 186 gigatons respectively). The authors worked out that this would need a carbon dioxide price of $52 per ton, see Gasification of coal and biomass as a net carbon-negative power source for environment-friendly electricity generation in China

This is all proven technology that we can certainly scale up and use worldwide if needs be later this century.

So, the IPCC were not just interpolating straw man proposals here. These are real possibilities that politicians could choose. But more expensive, and more difficult for sure than the path the politicians did choose to make their aim.

They also presented another example pathway to 2°C that involved ramping down by only 25% (10 - 30%) by 2030 and down to zero emissions by 2070 (Technical summary page 33) .

There are many other possible variations. The IPCC did not say what we should do of all these possibilities, did not say we have to stay within 2°C, or 1.5 °C, and they did not say that the biofuel burning carbon capture and storage is impossible.

They also made it clear that these are projections, not exact predictions. This is one of the main graphs they showed, which also showed the amount of climate uncertainty for the 1.5°C path. The science just isn’t there to predict it more exactly than this. In addition, there are built in natural variations in climate such as the Atlantic and Pacific multi-decadal oscillations which average out eventually, but only on a timescale of about 30 years.

The report also says that if we continue at the "Current warming rate" through to 2030, we may reach 1.5°C between 2030 and 2047 (that time interval is not shown on this graph).

The authors of the paper in Nature assume that the 2030 deadline that is so often repeated in the media stories about the IPCC report comes from the earliest date in that error margin. They are not the only ones to say that. Myles Allen also says so in his article in The Conversation.

However, I haven't seen any journalist reports that use quotes from the report or section numbers to back up that figure. So, it's hard to know for sure. It may be based on the 45% reductions by 2030. But if so, that is certainly not any kind of a hard deadline. It's one way to stay within 1.5°C, but especially if you permit overshoot there are many other possibilities, and even more if you aim for 2°C

Perhaps there is no way to find out for sure where the 12 years figure comes from.

As soon as we reach net zero emissions, the temperature steadies. Theoretically if we stop suddenly there is a fraction of a degree overshoot because we remove the masking aerosols from fossil fuel burning, but this is less than half a degree.

In practice by the time we reach net zero then the aerosols are down to around net zero also (Chapter 1, 1.2.4). They remark that we can ease the transition by targeting removal of soot first (which is warming). It's important to reduce methane emissions as we approach net zero, which will also help prevent overshoot due to suddenly stopping the aerosol emissions.

Depending how we do this and what type of world we transition to, the masking aerosols might even increase. For instance, if our world has a large amount of biofuel burning, then these produce similar aerosols to fossil fuels (which originally were biofuel after all). A nationwide study in Norway found that the cooling aerosols and albedo effects from the widespread use of wood burning stoves offsets 60 -70% of total warming effects from the CO₂ emitted by the biofuel burning.

If we ramp right down to the point where anthropogenic emissions are more than balanced by the terrestrial and ocean land sinks, then the CO₂ levels go down, and if we had no anthropogenic emissions at all (or all our emissions captured directly at source), then from then on CO₂ levels in the atmosphere gradually fall and very slowly the planet cools back down again, rapidly at fast (perhaps a quarter of a degree in 50 years), but then more slowly over centuries and millennia.

There is an overshoot, if we were to stop emissions abruptly, or possibly so, but their best guess is that it is only a fraction of a degree (see for instance the yellow curve in Global Warming of 1.5 ºC - chapter 1, figure 1.5) for a couple of decades followed by cooling reaching a quarter of a degree cooler by 2100. In a more realistic situation where we ramp down more gradually, by the time we reach zero emissions there are no anthropogenic masking aerosols left and the climate immediately starts to cool down slowly. The rising sea levels do continue, but not as fast as if the world was warmer.

The temperature can ramp down faster if we can do carbon capture and storage.

There are likely to be many more ways to do this in the future within a few years. We may also be able to make cement from the CO₂ (which is a double win, because the cement industry is a major source of CO₂ emissions currently), and use it productively in many other ways. For current pilot projects exploring this, see The COSIA Carbon XPRIZE Challenge but most of this is not yet proven on an industrial level.

(click to watch on Youtube)

Five of the ten are focused on carbon mineralization technology.

One of them is a team from Aberdeen that hopes use replace the entire cement industry with cement made through CO2°Capture. as a carbon negative replacement for ground calcium carbonate.

Their Carbon Capture Machine works much like the stalactites in caves, to precipitate the CO2 into calcium and magnesium carbonates as a replacement for Ground Calcium Carbonate (GCC) . If this works on a commercial scale it can decarbonize the concrete industry, responsible for 6% of the world’s annual CO2 emissions. That would be a $20 billion. industry transformed from carbon positive to carbon negative!

Carbon Upcycling makes new CO2ncrete from CO2 and chemicals, competing directly with the $400 billion concrete industry - in places like California with a carbon tax and mandate for low carbon building materials.

CarbonCure Technologies injects CO2 into wet concrete while it is being mixed. They are already in commercial use with 100 installations across the US, retrofitting concrete plants for free then charging a licensing fee. It may take up to 20 years to be used on scale for reinforced concrete, because that’s needed as a durability testing period.

For more on this see Between a Rock and Hard Place: Commercializing CO2 Through Mineralization

So why didn’t they speak up when the journalists so radically misrepresented the main conclusions of the report?

I hear this a lot from the scared people who contact me. I am one of the few who speak up in my blog posts about all this, and people say to me, why is it only you saying this, and a very few experts? Indeed the only author from the IPCC who has spoken up about it, that I know of, is Myles Allen. See his article in “The Conversation”:

However, he is speaking as an scientist, and not as a spokesman for the IPCC. Why don’t the IPCC say this?

That’s where this new paper comes in. It is called Why setting a climate deadline is dangerous and it says in its subtitle / short abstract:

The publication of the IPCC Special Report on global warming of 1.5°C paved the way for the rise of the political rhetoric of setting a fixed deadline for decisive actions on climate change. However, the dangers of such deadline rhetoric suggest the need for the IPCC to take responsibility for its report and openly challenge the credibility of such a deadline.

You can read the new paper in Nature through the link provided on the website of one of its authors, through ShareIt - the Nature sharing initiative: Why setting a climate deadline is dangerous.

The IPCC maintain a very strong separation between science and policy makers. The report is written by scientists, as is the technical summary which most scientist readers will use, but the “Summary for policy makers” in its final form is written entirely by governments, with the IPCC not even taking part in the final drafting of it.

The IPCC feel that this is important, that they are seen as standing above any political debates, activism, climate denialism, doomism and just present the straight facts.

They also do not do any scientific research as part of the report, rather, they summarize the scientific research in their field in a high level systematic review.

This is a method that originates in medicine as a way of finding out the best current understanding of research in a changing complex field.

So, what should they do when they are seriously misrepresented by journalists, activists and politicians?

If they speak out, won’t this blur the line between science and politics? Would this impact on the credibility of future IPCC reports? It is a very important point, and the authors agree that this is an issue.

However they have been so badly misrepresented by the media and activists, that the authors argue that to stay silent in this situation is the more political thing to do.

The authors present several negative consequences of not speaking up. I will go into this in detail in my summary of the paper later on, but one of the main ones is that if we do not stay within 1.5°C, then by their own predictions, the dire consequences the activists and doomists predict will not happen. This then would damage the credibility of the IPCC, even though they never said these things. You can see how this works by a couple of the comments on my own article below - in an early version the title was confusing and readers thought I was saying that the IPCC should challenge itself and their response made it clear that the IPCC had already lost credibility in their eyes through these climate deadline statements even though it never said them.

Their silence is being interpreted widely as a tacit approval of what the journalists say about the report. It seems to many that they are supporting the deadline-ist framing of the report.

Journalists have not reported this paper in Nature and are just ignoring it. As far as I know this blog post is the first mention of it in the news, at least the first page of Google News.

Now many journalists are “upping the ante” and saying we have only 18 months, with the implication that if we don’t do very drastic action by 2020, then civilization will collapse and humans likely go extinct.

Here is how the BBC is reporting it:

The sense that the end of next year is the last chance saloon for climate change is becoming clearer all the time.

"I am firmly of the view that the next 18 months will decide our ability to keep climate change to survivable levels and to restore nature to the equilibrium we need for our survival," said Prince Charles, speaking at a reception for Commonwealth foreign ministers recently.

This is UTTER NONSENSE. And I have a great deal of respect for Prince Charles, but if you read what he said in context it is absolutely clear that he was speaking in hyperbole here, like the way you say that “I could eat a horse” when you are very hungry (it is literally impossible for a human being to eat a horse in its entirety, there is not enough space in your stomach). His main message was a positive one.

I unpack his statement a bit in my article:

The eighteen months here is just the time until the next opportunity to renew the Paris pledges in 2020, something they do every 5 years by the Paris Agreement. Some, and perhaps many countries will already commit to 1.5°C in 2020, but realistically there will be a fair few can't or feel they aren't ready for it - no problem. Most will increase their pledges somewhat, reducing our expected global temperature rise a little more - and then as they get more experience implementing their pledges they can commit further in 2025, 2030 and so on.

That was one of the important innovations of the Paris agreement. Countries pledge to commitments that are ambitious but feasible, then as they gain experience, which can include winning over venture capitalists and private citizens buying renewables, starting new industries for electric cars, and renewables, retraining workers for the new industries, changing habits of their citizens, get experience running their first ever multi-gigawatt renewables power stations, and so on. Meanwhile the technology benefits from new research and economies of scale, and prices of renewables fall. After five years of this, it's expected that they find that they can increase their pledges, and again, and again. And this is indeed happening, many pledges will definitely be increased over the initial targets.

Prince Charles was just saying he is optimistic that there will be major improvements already by 2025, and as examples he mentions substantial new initiatives to increase private sector funding for sustainable development throughout the Commonwealth.

As you see, journalists take public figures words out of context, and they also use very emotive words such as that this action is needed for our very survival. Many of our youngsters, and adults too, take this quite literally, and I know that from things they say to me privately and also publicly in our Doomsday Debunked Facebook group set up to help them. Believing these journalistic exaggerations, they think that by the time they reach adulthood, in a little over a decade, the world will no longer have any humans in it, and that our civilization and species will be gone.

This is why I think it is a responsibility for science bloggers like myself and journalists to speak up against this.

David Attenborough is another very respected public figure who has been inadvertently encouraging this doomist framing by some of the things he says, You can watch it here: Attenborough presents Climate Change - The Facts

Standing here in the English countryside, it may not seem obvious, but we are facing a manmade disaster on a global scale. In the thirty years since I first started talking about the impact of climate on our global world, conditions have changed far faster than I ever imagined. It may sound frightening, but the scientific evidence is that if we have not taken dramatic action within the next decade, we could face irreversible damage to the natural world and the collapse of our societies. We are running out of time but there is still hope. I believe that if we better understand the threat we face, the more likely it is that we can avoid such a catastrophic future"

Strictly speaking it is not true. He says it is based on scientific evidence but gives none. Nor did any of the people he interviewed in the program say this. It seems to be an example of a “climate slogan” which is simplified to present a more powerful simple message.

In the documentary he gave examples of the California fires, which did involve people leaving their houses but only because they burnt down and they would surely return and rebuild.He also talks about rising seas displacing hundreds of thousands of people from coastal cities, and flooding. Perhaps this is all that he means by it. Climate migrants. After all he didn’t give any other examples. He didn’t say “collapse of all our societies”. Or “collapse of civilization”.

However whatever he meant it has been widely reported as a collapse of civilization

If you listen to what the IPCC themselves say, they do not talk about a risk of human extinction or collapse of civilization. There is no mention of such ideas anywhere in the report, or the press conference the journalists attended, their responses to questions or the short summaries by the co-chairs.

I’ve been one of the few who appear in Google News search results speaking up against this starting with my

The IPCC give an example of a worst case, one of their scenarios from chapter 3 of the 2018 report. No human extinction, nothing about collapse of civilization. We feed everyone through to 2100, though with less food security. Much of our natural world is still here, the majority of the species survive, and it is not a desert. It is not a world without insects. However the corals are nearly all gone, many areas of the world face problems, severe loss of biodiversity, and increasing rather than decreasing world poverty by 2100.

This is a scenario where somehow, despite everything, the Paris agreement was to fall apart completely. We act too little too late, in an uncoordinated way, and only just scrape in at 3°C by 2100 (it is not plausible that we don’t act at all, as these things happen). At present we target 3°C with our pledges, but with a lot of leeway to improve on that Their description for 2100 in this example worst scenario (which we are not on) is:

“Droughts and stress on water resources renders agriculture economically unviable in some regions and contributes to increases in poverty. Progress on the sustainable development goals is largely undone and poverty rates reach new highs.”

“Major conflicts take place. Almost all ecosystems experience irreversible impacts, species extinction rates are high in all regions, forest fires escalate, and biodiversity strongly decreases, resulting in extensive losses to ecosystem services.”

“These losses exacerbate poverty and reduce quality of life. Life for many indigenous and rural groups becomes untenable in their ancestral lands. The retreat of the West Antarctic ice sheet accelerates, leading to more rapid sea level rise.”

The details are here:

Things have changed a fair bit since they wrote that. I think a new "worst case" would be rather different. It's not plausible any more that we scrap the Paris agreement. It was momentarily touch and go in autumn 2018, when they were deciding the rule book, when there was trouble getting agreement but they did find a way ahead on the last day. So, now we have the framework, the rule book by which to do the accounting of the effects of the voluntary NDC's and there is nothing else technically to stop it.

If we did scrap it somehow, again that worst case is implausible, because renewables have gone down in price significantly even since the 2018 report. Also, the momentum we have now is hard to imagine reversing. As I said, China is expected to strongly increase its pledges in 2020, the UK obviously will, EU likely to, we can expect that 3°C figure to come down a fair bit after 2020, and then we have 2025 and 2030 to get onto the 1.5°C track, and if we have reduced it somewhat but not quite enough by 2030, we can still get on track with a faster ramp down, say, from 2030 to 2045 (depending on how much margin is left, and how much we have managed to sequester through recovery of degraded lands etc.).

Some of you may have been influenced by David Wallace Wells. He is not a climate scientist, indeed, not a scientist at all. He is a general journalist who only became interested in climate change two years ago, for the first time. His first article on the topic was widely slated by climate experts as containing many misunderstandings and exaggerations. He went on to expand it into a book, and this is what is scaring people. For details see my:

Another recent story that may have scared you is this “think tank” report by two businessmen, with no scientific credentials.

It uses David Wallace Wells as a source along with many scientific papers that they misunderstand. It clearly never went through any scientific peer review, they can’t have even got a climate scientist to give it a quick check over.

As examples of their many errors, they describe a paper about future heat waves such as we have had in Europe in 2019 and previously for instance in 2003, as about conditions of "lethal heat conditions, beyond the threshold of human survivability,".

They unearthed a figure of a figure from an old report of a billion people affected by a sea level rise of 25 meters (way beyond anything possible this century) and claim this is the number of climate migrants we will have by 2050 if we reach 3°C by then. It’s not even the same topic. If you get a sea level rise you can protect against it with sea walls, and 25 meters is more than ten times the expected sea level rise by 2100 even with the worst of the scenarios.

Michael Mann did speak up against that one. But few people said much, they just ignored it. Meanwhile I was bombarded by questions from scared people in Doomsday Debunked who believed this thing hook line and sinker. Though the BBC didn't run it, CNN did, as did the Independent, and Livescience, and a number of other widely read sites, shame on them!

This is a paraphrase of the executive summary of Chapter 3 - I have covered most of the points, though left out some that had significant overlap with earlier points.

To find out more I recommend reading the exectuive summary of chapter 3, Impacts of 1.5°C on Natural and Human systems. For those with a less scientific background see the section Projected Climate Change, Potential Impacts and Associated Risks in the summary for policy makers.

The awful Australian report also covered this article, which is often cited in this context:

It is peer reviewed. However that doesn't’ mean it is “right”.You need to think of these papers like a conversation. If a paper is published means that someone has a sufficiently well argued point of view to pass peer review as something that other scientists will read with their coffee in the morning and then discuss. And discuss it they did, and the general conclusion was that the climate change scientists, whose work is summarized by the IPCC just follow the scientific method, as does the IPCC itself in summarizing the work.

When the evidence so far is incomplete, and the systems hard to model, they have to try to fill those gaps, and sometimes they err in the direction of under estimating effects, as happened with the Arctic ice projections (now fixed).

However, they go where the science leads them in its current form. Sometimes they over estimate as happened with the carbon budget estimates before the 2018 report. The IPCC report’s occasional errors go both ways too, with perhaps the biggest of their rare mistakes, an error in the 2007 report when they said that all the Himalayan glaciers would be gone by 2035. See my

Florida is severely impacted by future sea level rises. If we get as far as a 1.8 meter global sea level rise, then according to one study, there would likely be 2.5 million Florida residents migrate away, most from Miami. 250,000 would likely leave San Francisco and nearby areas. Meanwhile Texas could see an additional 1.5 million immigrants, just because of the sea level ri se.' We're moving to higher ground': America's era of climate mass migration is here

The Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact was formed to look into ways to mitigate this in 2010.

Interview about it here with two scientists, the first is d Susy Torriente, chief resilience officer and assistant city manager for the city of Miami Beach talking about what they are doing in Miami.

I go into this in detail towards the end of

Bangladesh is already hard hit by climate migrants.

The poorer countries are more likely to solve it by internal migration. An estimate for Bangladesh finds that 0.9 million people of its population could be displaced by direct inundation by 2050 and 2.1 million by 2100, almost all of this in the southern half of the country. As well as sea level rise - about half of those in the urban slums were displaced by river bank erosion and river flooding. This is because of the way rainfall increases and becomes more erratic with climate change, and also the melting Himalayan glaciers affecting river flows. They also are affected by stronger cyclones in a warming world which damages infrastructure.

Every day 1000 to 2000 people migrate to Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka - and almost all of them when asked say they migrated because of the changing environment.

However Bangladesh is also spending considerable amounts on climate mitigation and adaptation. It spends $1 billion per year on climate change adaptation - a lot for a poorer country. That is 6 to 7 percent of its annual budget.Three quarters of that money comes directly from the government, only a quarter from international donors. The average European emits as much carbon in 11 days as a Bangladeshi in a year. For poorer Bangladeshis, the climate change bill per year often reaches as high as double their annual income, and poorer communities there are picking up crippling debts. So the costs of climate change are already hitting Bangladesh hard

Bangladesh would need about $3 billion a year by 2030 for climate adaptation, and $2 billion to mitigate against effects of climate change. So far the average domestic and external investment combined is $1.3 billion leaving a $1.7 billion funding gap. However Bangladesh is seen as an example of a country that is doing a lot to combat climate change.

Because of their similar situation, Bangladesh has support from the Netherlands in several projects, notably the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 (BDP 2100) by knowledge transfer, and support of the institutions responsible for delta planning. It will be financed internally up to a level of 2.5 per cent of GDP per annum by 2030 of which, 2.0 per cent of GDP would be from public funding and 0.5 per cent would be from the private sector.

Rebecca Eldon, who researched into Bangladesh’s NDC for her thesis, puts it like this:

Since my first visit to Bangladesh, the country has stood out to me as one of the most unique places in the world. There is incredible beauty, seen both in the population’s love for art and culture, and in the deeply rooted kindness and hospitality people show to one another. At the same time there is heart-breaking poverty, which is exacerbated as Bangladeshis experience some of the most severe impacts of climate change in the world.

Netherlands is fine because they are high technology and already have protection which they can raise as the sea levels rise. Sea walls can be indefinitely high - the world's highest earthworks dam is 300 meters high. Some places like Florida have limestone bedrock and can't keep the sea out with dams because it is porous to sea water. Their only solution is to build up on stilts, or to have sacrificial ground floor rooms that flood during tidal surges and king tides, together with raised roads or to build up the land itself.

For more details on Florida and the Netherlands see the end of my:

The Green Climate Fund is supposed to be $100 billion a year worldwide according to the Paris agreement with voluntary contributions from the developed countries as well as voluntary transfer of advanced technology to help with mitigation. Of course the US has withdrawn from it, that was one of Trump’s reasons for leaving the Paris agreement that he didn’t want the US to commit billions of dollars to this fund that only helps other countries and not the US (though of course indirectly the fund benefits everyone - a world with other countries in good economic state and with fewer climate migrants is a world in which the US benefits too).

But China has recently affirmed a commitment to the fund which is significant, not disclosed a contribution amount yet, that’s for the next 2020 meeting (until recently it counted as a developing country, now it counts as a prospective donor to such a fund). Hopefully others will increase their contributions by then too. And of course a future US president can rejoin or Trump can change his mind. It is under funded, only a tenth of it funded so far but in future hopefully it can be fully funded.

Actually the situation is very positive.

As I wrote about before in my Positive Side Of Climate Change Facts - After Two Years Of Climate Change Action, Heading For 3°C With 1.5°C Well Within Reach:

Almost nobody seems to report the positive side of our recent climate change action. As someone who followed the topic before Kyoto, what happened since 2016 was remarkable. The change in attitude, pace of action, at last gives much hope that we can rise to the challenge. I have never in my life seen such a coming together of nations worldwide to solve a problem.

Since then, written in April, 2019, only three months ago, the progress has continued to be remarkable. Scotland has already pledged to carbon zero by 2045, the UK by 2050, and the next President of the European Commission - or likely to be, Ursula von der Leyen’s proposed green new deal will make Western Europe the first 1.5°C compatible continent if passed.

All the leading Democrat candidates for the US elections in 2020 have election pledges that are at a minimum 1.5°C compatible. Whether they win the election in 2020 or not, climate change has entered US politics in a way that it never has before. The topic was not even mentioned throughout the 2016 campaign, and paradoxically, Trump with his rejection of the Paris agreement has probably been a significant factor in the US and the world, in bringing climate action right to the top of the political agenda.

In the US, as in Europe there’s a youth movement in the US, the Sunrise Movement, the activists who occupied Nancy Pelosi’s office

(click to watch on Youtube)

These are our future voters in the US, and their voice will get louder, not weaker, in future elections. Just as we have a green new wave of voters in Europe, which swept the EU elections, there is one in the US too. This is a movement that is not going away and will be a factor in all the future US elections from now on, as more and more young people of the current generation grow up and get the vote, and the effects of climate change become increasingly obvious to the adults too. If they do not succeed in 2020 then there are the elections in 2024, and 2028.

China is currently targeting a 20% non fossil share by 2030, and there were reports that it is expected to target 35% of electricity from renewables by 2030 according to drafts for its next plan, the “Renewable Portfolio Standard”.

Then China together with France also made a series of pledges on 29th June 2019

They agreed to on the importance of zero emissions, to update their pledges in 2020 as a progression beyond the current pledges, the importance of maintaining biodiversity, and the need to fully fund and support the $100 billion Green Climate change fund and advanced technology transfer to developing countries to help them mitigate climate change as well as adapt to it.

Some of the main points:

Carbon brief's comment on this is here: China pledges to strengthen climate plan

Another study finds that China is already on its way to peak emissions earlier than it pledged to (its current pledge is to peak before 2030). This was based on a study of its cities. Bejing peaked in 2007.

This study found that the decarbonization of Chinese cities depends on their GDP, that as the GDP increases, decarbonization is easier (a pattern found in other countries too). If the country as a whole progresses in the same way as the cities, China's emissions may peak between at 13–16 gigatons of CO₂ per year between 2021 and 2025, approximately 5–10 years ahead of the current Paris target of 2030.

That study is here

Carbon Brief's comments on that study are here:

China’s emissions ‘could peak 10 years earlier than Paris climate pledge’

China has built a major new renewables industry, with vast solar farms, hydro power and UHVDC power lines linking the renewables together across the country.

The world's largest solar farm, from space

The 850-megawatt Longyangxia Dam Solar Park. It is built right next to a big hydropower dam - because then in the day when the sun is shining the power comes from the solar powers and the dam ramps down. At night then the dam then releases the water it held back during the day.

This more than doubles the power output from the hydro electric and because the hydro can store power until it’s needed, like a giant battery, this means there is no curtailment - it never produces more power than is needed.

Prices of solar panels and wind turbines continue to fall, faster than previous estimates, and of batteries also. The Committee on Climate Change’s report: Net Zero The UK's contribution to stopping global warming, puts it like this:

One of the most positive and important developments since 2008 has been the very rapid cost reduction that has accompanied the global expansion of renewable electricity generation (especially for wind and solar power) and an accompanying fall in the cost of batteries.

They share this remarkable graph of the current and near future projected costs of onshore and offshore wind, and of solar-PV in the UK - both Solar-PV and the onshore wind are actually already competing with the lowest cost fossil fuels, without subsidies. Offshore wind is rapidly headed that way too. And this is for the UK which spans 50 to 60 degrees north, yet already is able to produce solar PV power competitive with fossil fuels:

The price drop for solar is especially remarkable, a drop from 2012 to 2022 from 27 to 4 cents per kilowatt hours. That's a huge reduction in just a decade. It's now competitive with even the lowest priced fossil fuels, it costs less to supply the power from solar even in the UK, 50 to 60 degrees north. Before 2015, only four years ago, solar power couldn't compete even with the most expensive of fossil fuels without government subsidies.

And - yes we can have a power system entirely based on renewables. We don’t actually need coal fired power stations or nuclear power to balance the variable output of renewables. Indeed those can’t ramp up and down fast enough. We can use fuel cells or molten salt to store power. Once electric vehicles are commonplace, they could earn money for their owners all the time they are parked, by automatically buying excess power from the grid and then selling it back again when renewable power levels are low. However, the easiest and least cost way to provide the peaking power right away is through hydro power, pumped hydro which can respond instantly and has vast potential (including using water pumped between lower and higher levels in disused mine shafts).

This debunks a myth about renewables - we have plenty of space for them, and they do not take away good agricultural land or land for conservation, not if done properly. Solar panels raised above the ground can be mixed with agriculture, they can be built on house roofs, on brown fields, on low conservation value areas of desert, or floating on canals, lakes and other waterways (especially useful in hot dry conditions as they help reduce water loss through evaporation).

One particularly useful synergy comes from putting floating solar on hydro dams, where it also helps to reduce evaporation and can double the power output of the hydro without any curtailment because of the way the hydro can rapidly respond as peaking power

And if you are concerned by effects on wildlife, it’s true that there can be effects, but this just means they need careful siting. The concerns are real and they do need care, but they are based mainly on very early examples of each, built before the problems that could arise for such installations were fully understood.

This is about those "toy models" you get sometimes where the researchers take a few equations and claim they represent the entire planet and predict disaster. It shows how you can have toy models like that that are sustainable too

If you have heard all the news about a "sixth mass extinction", this post may get you thinking, it's not as clear as it seems, there are actually winners as well as losers. Of course we need to preserve species as much as we possibly can. But we start with a very biodiverse world, more so than at most times in Earth's history and we face a future where according to some researchers, individual biospheres may actually be more biodiverse than now, much as probably happens when continents collide to form supercontients. This draws heavily on the work of Chris Thomas, whose book is well worth a read if you don't know it.

This is the UK’s current progress towards carbon reductions of 80% by 2050:

There the gray bars are levels enforced by law.

We are now going to tip that graph down to reach zero emissions by 2050, and by 2045 for Scotland.

China has continued to build lots of coal power stations, so also has India, to the point that we can’t stay within 1.5°C if we use them to capacity - but neither are expected to use them to capacity.

This is an insurance to make sure that they can withstand the transition as they rapidly industrialize. They produce far less CO₂ per capita than the US, even China has half the CO₂ emissions per capita of the US, meanwhile India has less than a quarter of China’s emissions per capita:

India remains on track to overachieve on its 2°C compatible target and 1.5°C is within reach India | Climate Action Tracker, see also Guest post: Why India’s CO₂ emissions grew strongly in 2017 | Carbon Brief

China faces the biggest challenge of all, it is expected to meet its commitments which include 20% non fossil fuel by 2030 and to peak emissions before 2030 but it has to increase its commitments for us to have a chance to say within 1.5°C. China | Climate Action Tracker

As they ramp up to full scale industrialization, the coal fired power stations have low start up costs and high ongoing costs. Renewables have very high start up costs, and low maintenance costs (compared to the high costs of fuel for the fossil fuel plants). Also, importantly, the startup costs for building them decrease rapidly year on year. Wait a couple of years before you build it, and you get a much higher profit margin on your new renewables power station.

With that background it actually makes economic sense to build a coal fired power station now, then a renewables power station a year from now that will take over most of the capacity planned for the coal fired one, producing its electricity at lower overall cost. This is especially so because of the need to ramp up to a whole new industry of renewables, and build the first large scale renewables power stations, and learn from them for the future ones. Another factor is the difficulty of encouraging the businesses of India and China to invest in renewables with its high start up costs, and the return on investment only years later. This is a particular dilemma for countries like India and China, when there is a shortage of venture capital. Also, in those countries, most people do not have high levels of savings, for instance for roof top solar. Renewables is still seen as risky by many investors in India, and one of the main roles of the Green Climate Fund investment in solar rooftop technology in India is to convince local people that it is worthwhile to invest in renewables and that you will get a good return on your investment.

This DOES NOT MEAN CHINA AND INDIA ARE INSINCERE about ramping up their pledges. China and India are amongst the most affected, and are strongly motivated to do their darnest to address climate change, and are showing by action that this is a top priority for them.

See my

As I said in my Positive Side Of Climate Change Facts

The pace is accelerating. Month on month it may seem glacially slow, but over a few years, extraordinary. We can do this!

There’s a pervasive idea in our society of an almost impossible situation, that we can’t do anything about climate change, or that nobody is doing anything, or that we are headed for a doomsday scenario and it is almost over, already. None of that is true, not remotely so.

In the intro I mentioned how Myles Allen, a lead author for the IPCC report in 2018, spoke out about this in : Why protesters should be wary of ‘12 years to climate breakdown’ rhetoric in The Conversation:

Today’s teenagers are absolutely right to be up in arms about climate change, and right that they need powerful images to grab people’s attention. Yet some of the slogans being bandied around are genuinely frightening: a colleague recently told me of her 11-year-old coming home in tears after being told that, because of climate change, human civilisation might not survive for her to have children.

It’s so sad. To add to what he says here, we encounter kids like this in Doomsday Debunked all the time, scared sometimes to the point of being suicidal that they will not live to adulthood, and young adults who feel they shouldn't have children because they have read that they would be bringing them into a future uninhabitable Earth. A fair few are receiving therapy and drugs to treat PTSD and GAD and other anxiety disorders, and have panic attacks and vomit in fear many times a day. The sad thing is that much of what scares them so much is out and out junk science, exaggerated stories or these over simplified climate slogans.

Myles Allen continues:

The problem is, as soon as scientists speak out against environmental slogans, our words are seized upon by a dwindling band of the usual suspects to dismiss the entire issue.

I've come across this too. Even when the climate scientists do speak out, as they do sometimes, their views do not get the publicity - a story is far more likely to be shared on social media or run in the mainstream news if it says that all the insects will die, civilization end or humans become extinct.

Myles Allen,continues, in his : Why protesters should be wary of ‘12 years to climate breakdown’ rhetoric

Using the World Meteorological Organisation’s definition of global average surface temperature, and the late 19th century to represent its pre-industrial level (yes, all these definitions matter), we just passed 1°C and are warming at more than 0.2°C per decade, which would take us to 1.5°C around 2040.

That said, these are only best estimates. We might already be at 1.2°C, and warming at 0.25°C per decade – well within the range of uncertainty. That would indeed get us to 1.5°C by 2030: 12 years from 2018.

Indeed we may well temporarily go over 1.5°C in the very near future. Not in 10 years, it could happen as soon as five years from now.

But that is climate variability, averaged over one year instead of the 30 years used for climate change projections. This is good science but would not mean we have “missed” the Paris agreement target. As Carbon Brief put it:

Such a breach would not mean that the world has “missed” the Paris Agreement’s aspirational target of limiting human-caused global warming to 1.5C

World has 10% chance of ‘overshooting’ 1.5C within five years

They go on to say, quoting an IPCC climate scientist, Rogetl, as interviewed by Climate Brief:

“International temperature targets are defined in ‘climatological’ means – that is global temperatures that are typically averaged over a period of 30 years. So exceeding 1.5C in one given year does not mean that the 1.5C goal has been breached and can be discarded. Actually, this is precisely what we expect when approaching a global warming limit of 1.5C.”

And at the end, again quoting Rogetl:

“It is important to note that governments support a 1.5C temperature goal because they consider that to be a level of warming that is acceptable or safe for their citizens and societies. Breaching that level of global warming does indeed mean that we failed to limit warming to that ‘safe’ level, but does not mean that climate change should suddenly go unchecked. The world doesn’t end at 1.5C, but, at the same time, science also shows us that severe impacts are already to be expected at 1.5C of warming.”

World has 10% chance of ‘overshooting’ 1.5C within five years

Myles Allen puts it like this:

But an additional quarter of a degree of warming, more-or-less what has happened since the 1990s, is not going to feel like Armageddon to the vast majority of today’s striking teenagers (the striving taxpayers of 2030). And what will they think then?

It's not impossible that we reach 1.5°C by 2030, that it's within the range of uncertainty. If we do hit this level, the world will feel much as it does today to the majority of the population of the Earth.

Myles Allen goes on to say that

"the IPCC does not draw a “planetary boundary” at 1.5°C beyond which lie climate dragons."

...

So please stop saying something globally bad is going to happen in 2030. Bad stuff is already happening and every half a degree of warming matters, but the IPCC does not draw a “planetary boundary” at 1.5°C beyond which lie climate dragons.Why protesters should be wary of ‘12 years to climate breakdown’ rhetoric - by Myles Allen

This is a new paper in Nature saying the same thing.

The authors are

Mike Hulme, professor of human geography and department head at the University of Cambridge, who has a special research interest in how knowledge of climate change is constructed (especially through the IPCC); and interactions between climate change knowledge and policy, and has published many papers on climate change.

Shinichiro Asayama, visiting scholar at the department of Geography (lead author)

Rob Bellamy, Presidential Fellow in Environment in the Department of Geography at the University of Manchester, also author of this article in the Conversation, Should we engineer the climate? A social scientist and natural scientist discuss

Oliver Geden, sociologist and head of the EU/Europe Research Division at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) in Berlin who works on European Union’s climate and energy policy, climate engineering, and the quality of scientific policy advice.

Dr Warren Pearce, sociologist and senior lecturer at the University of Sheffield and member of the inaugural Board of Science in Public, the international cross-disciplinary network focused on the relationship between science, technology and publics.

You can read the paper itself here: Why setting a climate deadline is dangerous.

But it is written by scientists for scientists. The language may be intimidating for some, and I think it will help to do a paraphrase of some of the main points in less techy language.

They refer to the sensationalist headlines I already mentioned, the civil disobedience by the Extinction Rebellion, the declaration of a climate emergency by the UK parliament and the Green New Deal proposal in the US. They continue:

The world suddenly seems to have limited time in which to act decisively on climate change — and, if not, to be resigned to our climate fate.

They then explain some of the history that lead up to this rise of “Climate deadline-ism”

It began as a result of long standing scientific and political work to try to find out what is “dangerous” climate change. This was converted to a peak temperature, then a fixed carbon budget, and now, to a deadline, after which any attempts to do anything are said to be “too late”.

This helps to increase a sense of urgency - but it also creates a situation where a climate emergency is rashly declared with possibly politically dangerous consequences.

There, they mean, dangerous in the sense that it risks derailing the climate change action in the future.

So then - what is a responsible response for the IPCC to all this?

They then expand on these points.

First, there were various suggestions of targets to aim for - greenhouse gas concentrations, ocean heat content, or sea-level rise, but global temperature was what they finally decided back in 1992 was the best way to quantify a level of “climate change”.

From the mid 1990s through to 2015 the target was 2 °C. The 2015 agreement was first to introduce 1.5 °C, though at the time more of a rhetorical aspiration than a real future target.

However, mainly as a result of public campaigning in the last three years, the safe limit has now been reframed as 1.5 °C,

Then another thing that happened is that the scientists found that the future temperature is nearly exactly proportional to the amount of CO₂ added - that no matter if it is done over a year or 30 years, adding the same amount of CO₂ to the atmosphere leads to the same temperature increase. As a result scientists started to look at policies in terms of the total CO₂ emissions allowed to limit global warming to a given level.

This then lead to an approach that lets us estimate how many years remain to a particular climate target. Based on that, the IPCC estimated a range of 12 to 34 years from 2018 for the remaining time to reach 1.5°C, which is where the 12 year rhetoric comes from

This has now been turned into literal “clicking clocks” on the web. I know that some of my readers are especially sensitive to count down clocks - which is why I added the yellow text overlay (and also to help with any use of them serendipitously as images in social sharing).

And

Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC)

Note that both of them count down accurately to the centisecond, or hundredth of a second - yet they give different figures. As of writing this, the David Usher / Damon Matthews clock says 15 years, 4 months 6 days and a constantly changing number of hours minutes, seconds and centisecs while the Mercator one says 8 years, 5 months, 6 days and a constantly changing number of hours, minutes, seconds and centisecs.

It is obvious we do not know such a thing to this level of accuracy! In fact the error bar in the IPCC report was more than a decade, between 12 and 34 years. counting from 2018.

As they put it in the paper:

From a communication perspective, this translation is understandable. Neither global temperature nor carbon budgets convey any great sense of urgency to non-experts whereas time — and the associated notion of a deadline — is a metric that converts the abstract, statistical notion of climate change to a more recognizably human experience. Rather than degrees Celsius rise in temperature, or gigatonnes of CO₂ emitted, the ticking countdown clock sends an alarming message to the public of time slipping away.

I can confirm from my own experience that people find clocks like this extremely scary, and they can often trigger panic attacks (a scary experience for them, heart pounding, breathing fast). Indeed I wondered whether to include screenshots from the clocks at all here, bearing in mind my more vulnerable readers, but the fact that they count down to different dates, and the text overlays, should help there.

They then talk about various issues with using a clock metaphor and a fixed CO₂ budget for a deadline.

They describe various possible responses that would seem sensible decisions on the basis of the ticking clock metaphor but may not be the best for our climate future.

The next paragraph may be puzzling to you if you haven't followed the climate debates, especially since they use the short form of citation with just the names of the author and not paper titles.